# MFU is Poorly Approximating Billions of Dollars in Compute

*Model flop utilization beyond 6ND*

by [@bwasti](https://x.com/bwasti)

---

Model FLOPs Utilization (MFU) is ***the*** efficiency metric these days.

It captures the utilization of GPUs

either during training or inference.

In turn,

it effectively

quantifies the optimization opportunities available

on billions of dollars of compute.

And, for the most part, it's quite crudely estimated.

### Billions?

The world

[used ~415TWh of electricity across AI datacenters

last year (2024)](https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-and-ai/executive-summary). At a very cheap 5¢/kWh we're

talking over $20B in electricity alone.

This number isn't getting smaller.

### Naive?

The most common approximation for MFU is extremely rough:

$$

F_{i} = 2\cdot ND \\\\

F_{t} = 3 \cdot F_{i} = 6\cdot ND

$$

Where $F$ is model flops, $i$ is inference, $t$ training.

$N$ is the number of parameters in a model and $D$ is the

length of the input (or maybe output ... "sequence length").

### What's so bad about 6ND?

To derive $6ND$ we assume these three things:

1. every parameter contributes a single multiply-add (2 flops)

2. backward is 2x as expensive as forward (thus, 3x total)

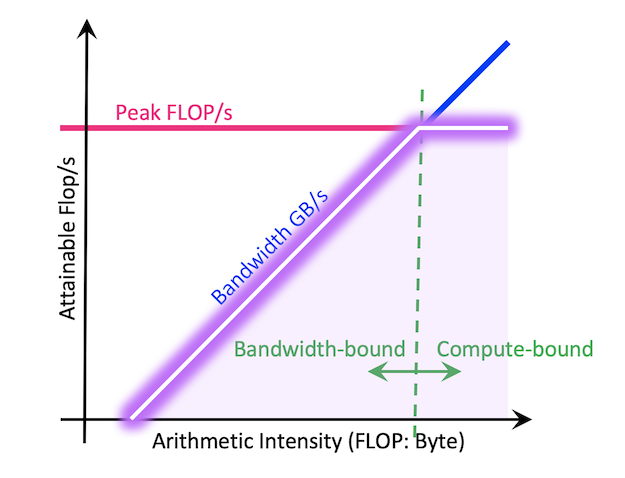

3. everything is [compute bound](https://docs.nersc.gov/tools/performance/roofline/)

Yea, the *main* optimization metric used on billions of dollars of compute

across the industry is typically heavily approximated by these assumptions.

Nuts!

### Issues *[[i.e. pedantic stuff]]*

Ok I lied 6ND is not dead. For small labs pre-training models,

the 6ND approximation is probably fine.

Why?

In those domains everything *is* compute-bound and FMA dominated (by

the FFNs).

That's what the approximation has lasted so long.

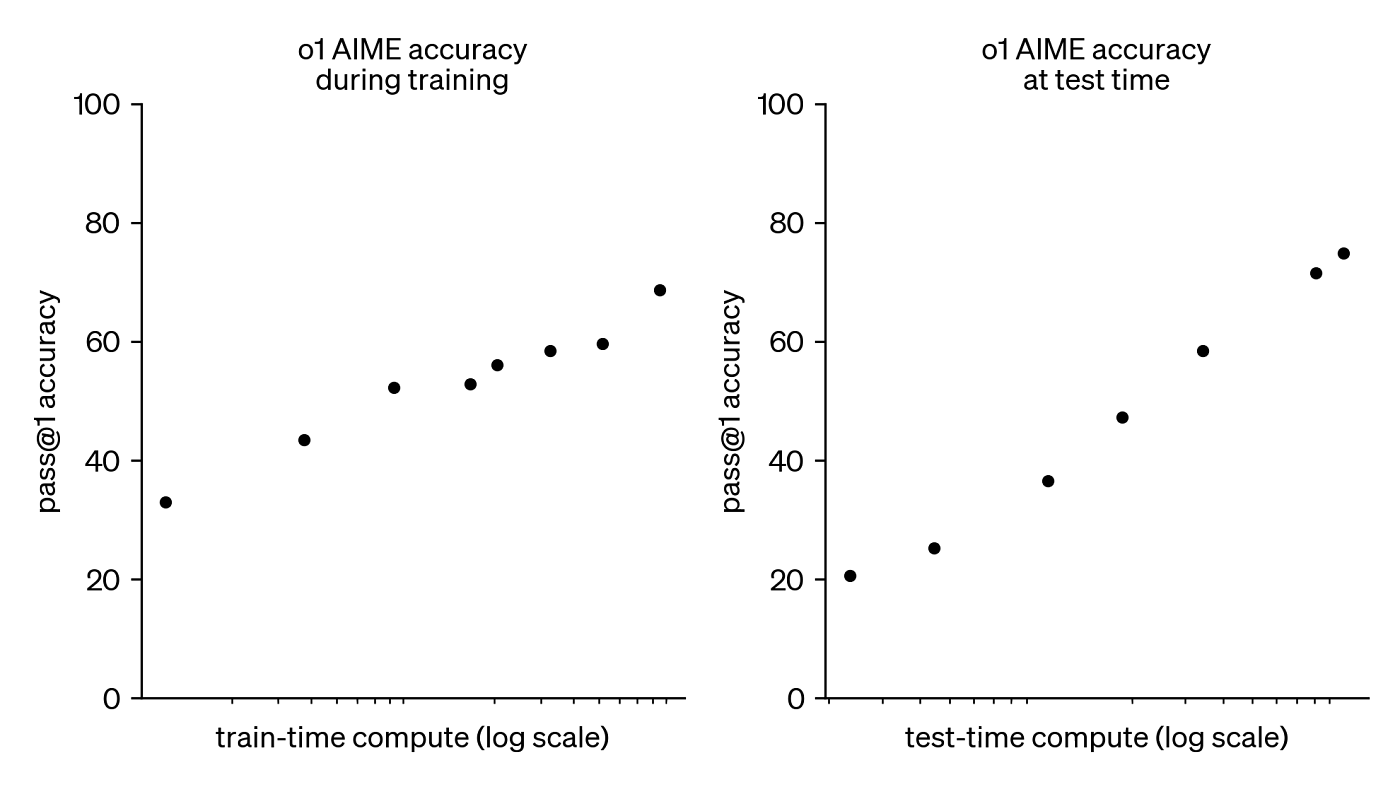

But most modern large-scale training is **inference-bound** (due to test-time scaling, see above).

Beyond that, product serving demand is growing as a rapid click.

For inference 2ND is definitely problematic. It rarely captures

the true MFU being achieved, since there are *so* many confounding variables.

***Attention is all I bleed***

First, and most trivially, $D$ is linear and attention is not actually linear.

However, if your sequence length is "short" (I'm talking thousands of tokens),

you are usually bounded by the [FFNs](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Multilayer_perceptron)

within LLMs. So fuck it, $D \approx D^2$.

When sequences get long (when is that? depends on the model)

we have adjust by the O($N^2$) attention scaling.

Keep in mind, this has to be done within each batch lane, so the true flop

count ends up looking quite complex.

Thanks [Horace](https://x.com/chhillee) for pointing that out!

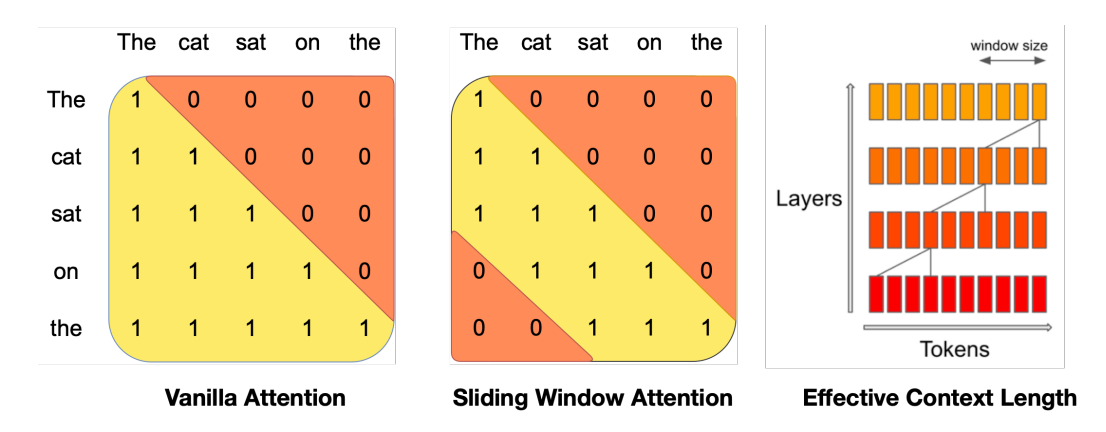

And what about more modern attention mechanisms? These often interleave

local attention to save on compute and induce context length generalization.

So we have to be extra careful when the sequence length get long!

***Mo' Experts Mo' Problems***

Mixture-of-expert models are all the rage and unfortunately that means

the trusty $N$ in our $6ND$ becomes a bit harder to calculate.

Instead of total parameter count, we need active parameter count.

Typically this is just a matter of keeping track of all the details,

which is rather tedious and bug-prone.

For example, OpenAI published gpt-oss's [total active is 5.1B](https://openai.com/index/introducing-gpt-oss/).

The total parameter count is 117B, the number of experts is 128 and 4 are active.

Ah so $4 \cdot \frac{117e9}{128} = 5.1e9$, right?

No, we're not properly handling attention weights and projection layers.

And be careful when shared experts are involved like Deepseek's MoE.

$$

S = \frac{E_{active} \cdot E_{shared}}{E_{routed} \cdot E_{shared}}

$$

In the above

$S$ is a sparsity factor you can use to adjust your $N$ per layer.

***Parallllellism***

Besides always breaking all the time,

training and serving on thousands of GPUs is a fantastically annoying thing to do

because there are *lots* of types of parallelism to manage.

Tensor (err, model) parallelism, pipeline parallelism, data parallelism,

context parallelism, expert parallelism (which is more of a meta-parallelism).

This might seem hard to account for with MFU calculations,

but it isn't. You just need to divide by the *total* parallelism given

the global size number of FLOPs.

Total parallelism is most easily figured out by counting GPUs rather

than multiplying the numbers above (since lots of paralellism overlaps these days).

***Batching Never Sleeps***

In inference no one waits to collect batches

of requests to run them all at once. That's a training thing.

Everything is done continuously by modern services,

which multiplexes and fields asynchronous requests as fast as it can.

That means, at any given point, your service will probably have some slack

built into it for that $(N+1)^{th}$ request. Similarly, your service

will constantly be running at different compute profiles as it becomes

under and overloaded. This creates a highly dynamic MFU!

***Disaggregation Nation***

Prefill and decode are different. As a result, modern services tend not to run them on the same

hardware. This creates opportunities to optimize them separately, so their MFU typically diverges.

Prefill is a lot easier to saturate with compute!

***KV-cache rules everything around me***

KV-caches at inference time mean your sequence length parameter

$N$ really only needs to capture the $N$ *new* tokens being

processed (either input or output).

***Speculative Investments***

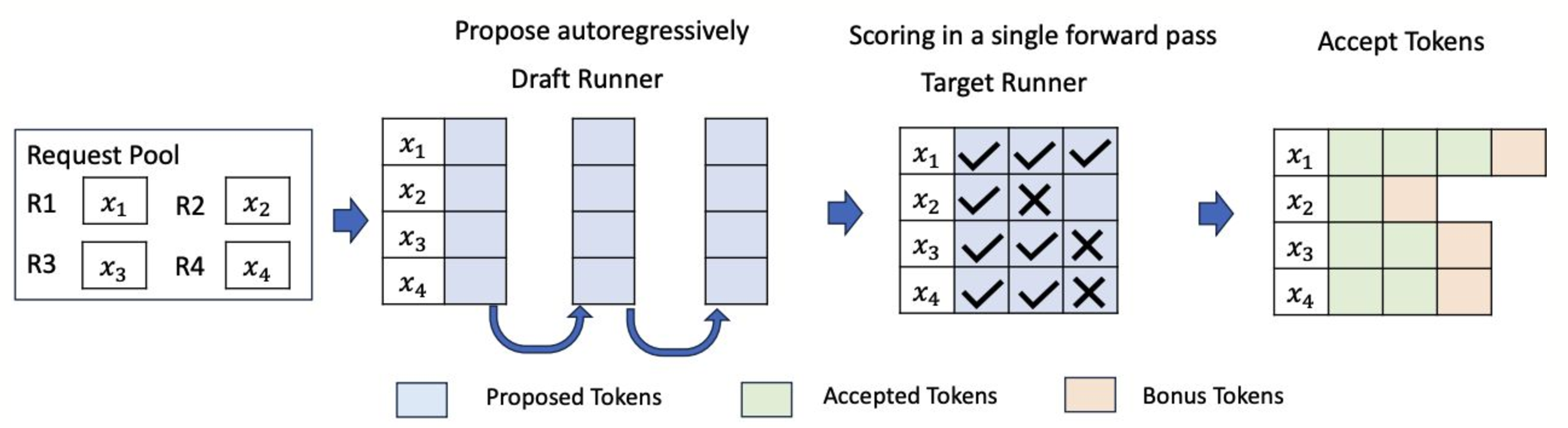

Another wrinkle in the MFU game is a fairly common optimization called

speculative decoding. This does two things:

1. Increases the flops by running a speculative model (and validating the speculation)

2. Produces a lot of useless tokens

If you don't consider the flops of the speculator,

this can yield an MFU over 100% (in theory).

Instead we should take the sum total output of flops and divide by validated tokens

to effectively subtract the "wasted" flops. Or maybe we don't consider them wasted?

Either way we have to be careful and clear in what we're measuring.

## Certified Professional-Grade MFU

To put some of these thoughts in action, let's build MFU into vLLM.

Here's a PR: https://github.com/vllm-project/vllm/pull/25091

The PR takes two approaches:

### First Approach: Simplistic ~6ND~ 2ND

All we try to do here is derive the active parameters.

That means we have to handle MoE correctly, but the rest is straightforward.

```

total_params = 0

for name, param in model.named_parameters():

module = get_module(name)

if isinstance(module, FusedMoE):

ept = module.moe_config.experts_per_token

ne = module.moe_config.num_experts

sparsity_factor = ept / ne

else:

sparsity_factor = 1

total_params += param.numel() * sparsity_factor

return total_params

```

This works well enough, but of course doesn't handle all the tricky nuances.

It is perfect for "are we way off?" type tracking.

It is also very quick -- you can probably run this every step,

but the PR caches it anyway. That means you can get MFU every single forward pass!

```

def analyze_model_mfu_fast(model, parameter_count, args, kwargs):

mfu_flops = kwargs['input_ids'].numel() * parameter_count * 2

return MFUInfo(mfu_flops)

```

### Second Approach: PyTorch Graphs

The second approach ditches efficiency (for now)

and attempts to build out a framework for extremely accurate MFU,

addressing all the concerns listed above.

The idea is that if you're scaling up machine learning workloads,

you're already using `torch.compile`.

Of course this is likely interleaved with fast hand-built kernels

and carefully scheduled communication primitives.

But regardless of the nuances in your exact usage and optimizations,

`torch.compile` gives you a beautiful thing: ***execution graphs***!

With these graphs you can iterate through nodes

that are well equipped with the information needed to

derive FLOPs and other goodies like

bytes moved.

For example, here is how we might define a linear node:

```

def mfu_linear(inputs, output):

M, K = inputs[0].shape

_, N = inputs[1].shape

flops = M * N * K * 2

read = get_tensor_bytes(inputs[0]) + get_tensor_bytes(inputs[1])

write = get_tensor_bytes(output)

return flops, read, write

```

But why return bytes written and read?

Recall the third assumption of the 6ND MFU calculation:

Not all operations are going to be hitting the compute-bound

region.

With this approach we determine which operations

*shouldn't* be maximizing flop utilization

and come to more realistic and insightful conclusions about performance gaps.

This leads to final comment I'd like to make.

# MFU is a good metric and a bad guide

It is perfectly reasonable to track MFU

because it is almost always monotonic in a theoretical measure of optimal performance.

And, a single number to largely capture the

efficiency in both training *and* inference is quite nice.

But even with a more accurate MFU, it is simply not going to capture everything.

MFU doesn't carry across models or hardware, but, given these, it can be used

to compare frameworks.

It will let us determine which workloads run less efficiently and tune our configurations

accordingly.

But it does not pinpoint where we are slowing down:

which operations, which communication primitives which kernels.

I think we could improve MFU in two ways:

- Capture MFU per module, operation, or even kernel: allowing us to capture fundamental bottlenecks in profile traces.

- Incorporate roofline models to measure how close we are to whichever "ceiling" makes sense.

But this might be overkill.

Sometimes simple metrics are best, and I am probably

quite biased by my day-to-day work.

---

*Thanks for reading :) I haven't posted in some time and it means a lot.*